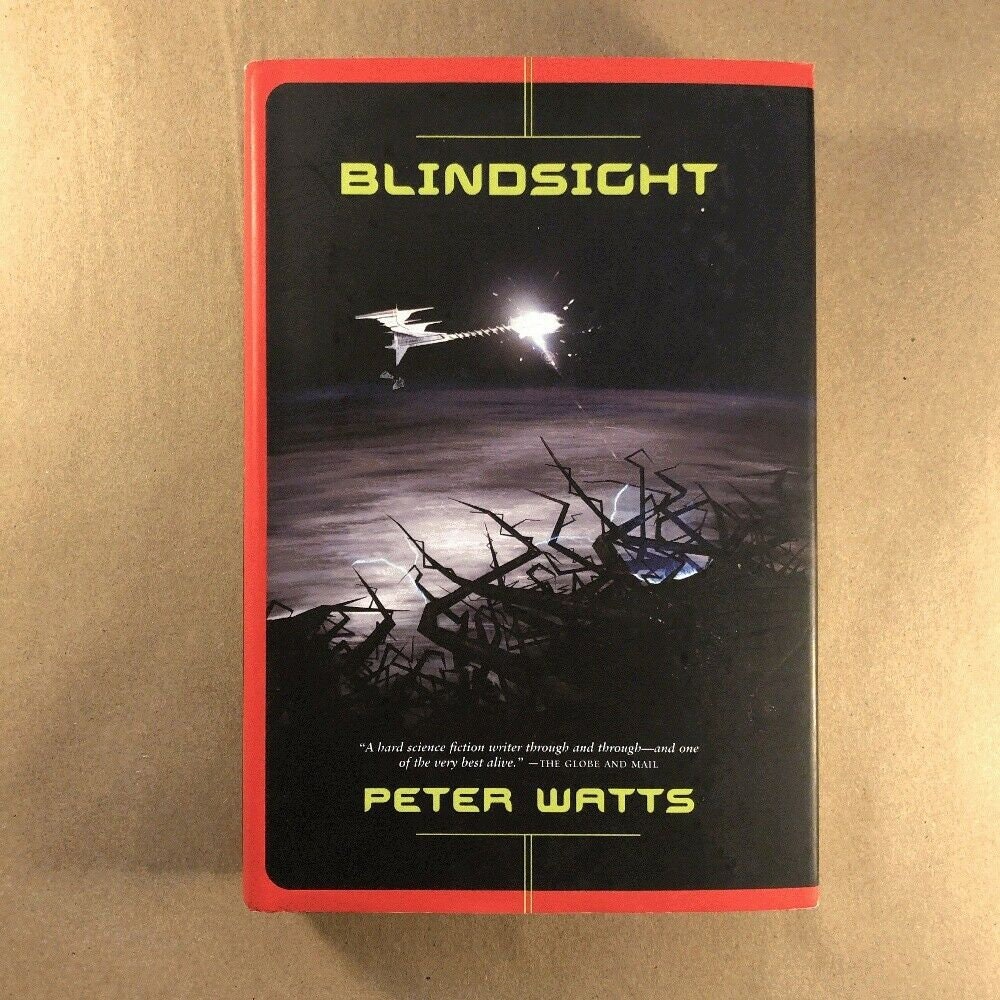

Watts’s description of the event is characteristic of the book as a whole: densely filled with detailed jargon, yet sleek and sharp because of that very precision of language fast-paced and poetic. These “Fireflies” quickly appear in Earth orbit, take a snapshot of our world - our technologies, communications and activities - broadcast that captured data out into space, and then burn up in our atmosphere. It is 2082, and Earth is shaken out of its contemplation of the Fermi paradox by the sudden arrival of tens of thousands of alien probes. That state of human self-satisfaction nicely sums up where Blindsight begins. It’s easy to see why this type of speculative fiction has become gauche in many circles: we like to think we know everything. At a high level, Watts is interested in how this evolution, our evolution, may play out he is as interested in what we don’t yet know about ourselves as what we do. Watts understands that life is not static, that we are part of a world, part of a universe, that is constantly evolving.

It’s no surprise that such a static, unchanging view of the world would be anathema to a writer like Peter Watts, an evolution-minded marine biologist by training. There is the pressure to see literature according to a single aesthetic, to judge it based solely on how well it captures our humanist understanding of a fixed present.

And we can see this in modern Western fiction, as the new game of literature is “the human condition” - showing what we know rather than grappling with what we don’t know. I imagine that within any given movement, though, there comes a time when some sufficiently large number of people - a majority in fact or at least in voice - decides that they’ve carried things as far as they want to, that any further change, any further speculating, is as likely to impact them for the worse as for the better.

What are those odd looking animals, where did they come from where did we come from what are those flashes of light in the darkness? Looking at the earliest stories we have record of, we can always see several purposes at work: stories existed to inform to entertain and, from the start, stories have existed at the level of myth to theorize, to suggest and test possibilities about the unknown elements of the world that we see and experience.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)